It is curious to see journalists and commentators bemoan the changing face of Dublin City. The people who accuse others of “fear of change” are ultimately à la carte about that change. As ever, the conceit is to glamorise the forms of liberalism and to bemoan the content. Just as democracy is lionised in principle and bitched about in practice, the vanguard forces of progressivism and liberalism keep the true implications of their worldviews at a safe distance. They lament the destruction of Georgian terraces in the 1960s that made way for ugly brutalism. But it doesn’t take much shaking of the snow globe to see those Georgian houses as problematic relics of an imperialist legacy and those brutalist monstrosities as the cutting edge of a socialist futurism. The bonfire of the past is one at which progressives tend, even if later they tend to the ashes.

When it suits them “change” is heralded as an absolute force for good. But only when it suits them. For the most part the people who surf the crest of social change, commentating on it or adjudicating on it, are the people most insulated from it. Long after the real damage is done to parts of society they hold in contempt, they themselves begin to irk at slight personal inconveniences. Finally, when their tea set shatters, they become perfectly sentimental. We see now that the scale of change in Ireland is so great (so accelerated and so far reaching) that it threatens even their ad hoc definitions of “community” and their timid definitions of “social cohesion”.

All Surface, No Substance

It is a surface anxiety. Closer to the abstract than to the tangible. They obsess over the trivial or the cosmic. To preserve Moore Street for its historical value while allowing laissez-faire immigration to change the whole demography of inner city Dublin shows a shocking lack of perspective. They have no notion of the world as something to be lived in; a place to bring up children in, a blood bond between the generations, to be defended street by street and house by house. Between humanity and the individual stands the nation, wrote Arthur Griffith, but no such construction exists in the landscape of contemporary morality.

Once you concede the idea of Dublin as a transient population, then you have conceded everything. You are at the mercy of global financial institutions and the local bureaucracies which service them. Once you accept the premise that massive demographic change over short periods is “culturally enriching” then you have no grounds to lament the changing architecture or the decline of social cohesion. What’s more you have absolutely no control over it. As the first Irish generation to experience such rapid change, you can pretend to be part of it. You can pretend that this is just an evolution in Irish society… that this is just cosmopolitan Dublin at its best. You can pretend that certain things you value will stay the same and that in the sea of globalisation you will find islands of cultural continuity. But these reassuring vignettes which you so cherish will be lost to the people who come after. Cosmopolitanism is itself transience. Even the highest moments of cosmopolitan creativity were but blips in time followed by kitsch.

An authentic Dublin is being lost, they tell us. The sense of atmosphere and of community is being lost, replaced with endless hotels and a corporate ethos. And who is to blame? Monolithic institutions like Dublin City Council and the greed of philistine capitalists? The old men and the old ways? The youth betrayed again? But what exactly did you expect? What did you expect from the future that is now the present?

Long March and Long Defeat

What is materialist is reductionist. We see this in every aspect of Irish life, from news to politics, from socialism to republicanism. Every new generation of dissident republicanism which defines Imperialism in a way that excludes most of the empires that have ever existed, moves further and further from the reality of history. The form (republicanism) has extrapolated the content (authentic nationalism) out of existence. So too has the activist Left put hollow forms above the organic nature of life and society — put the form of community above living community.

It has been the “progressive” project of the Left in this country since the middle of the last century to destroy the voting power of rural Ireland and of agricultural power in particular, replacing it with what were then vague dreams of an infinitely malleable urban proletariat. The latter has emerged as the transient international workforce that we see today which staffs the big tech companies that make their headquarters in Dublin. The opening of Ireland, the drive for foreign direct investment, the project of European Federalism, all dovetailed with this dream. The great leap forward as in so many socialist endeavours was capitalism itself. They supported the invasion forces because they saw allies. As a result, Ireland has become an occupied country quickly in the process of becoming a non-country. Dublin is increasingly a foreign city.

To paraphrase the words of Malcolm X, “We didn’t land on Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley landed on us.” The globalisation of Ireland or its assimilation into the global system has been an uprooting of all rooted experience. When we walk the streets of Dublin, we should not expect to see the reassuring or the familiar. We should expect to see the forms match the content, the representations of society match the nature of society. We should expect a foreign city to look foreign. We should expect a rootless society to look anonymous and corporate by day, dirty and empty by night. We should expect to see notions of community retreating into shadows and ghettos.

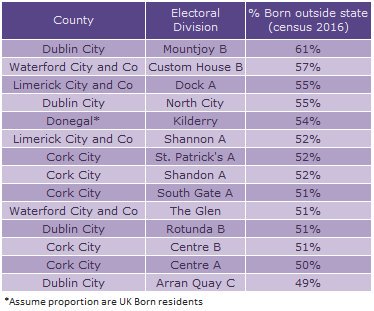

It is comical to see people march the streets to bemoan the destruction of local night spots when large parts of the inner city are majority non-Irish. If demography has no value then bricks and mortar have no value. Since “Irishness” is relative, it is a continuum of nothingness. Community is planetary. The local is global. We live in a society of strangers. Buildings are just investment opportunities for oligarchs. Home, like homeland, is an outmoded form. People from nowhere belong nowhere. The Dublin that so outrages Una Mullally is the Dublin she deserves. A garrison city of multinational headquarters and rental developments for single people.

Building the Utopia

Utopia is all too often the denial of nature itself with devastating and sometimes unintended results. The commentariat in Ireland today have no concept of an organic society so naturally every problem is a problem of bureaucracy. To put it another way, a problem of utopia-building. A problem of form, you might say, alienated from content. If only the right bureaucracy was in place, and funded with infinite resources, everything would be fine. It never occurs to them that since the bureaucracy would be staffed by people such as themselves, people who think as they do, that it would only institutionalise the failure. They do not acknowledge their role in the failure to begin with. Even the examples they point to as exemplars, demonstrate this vapidity. Pointing to specific social models in Sweden or Germany or anywhere you care to mention without so much as a thought for the human raw material or the centuries of inherited tradition that form specific habits of place. Models are just bureaucracies to them to be enacted at will upon arbitrary groups of people. But then a liberal’s reach must exceed his grasp, or what is Reddit for?

Utopianism of one sort or another is not rare in human history. Every attempt to create a rigidly communist industrial model has been a game of Whack-a-Mole with human nature. The natural order invariably intercedes. The aspects of humanity necessary to self preservation assert themselves. Nationalism, desire, belonging, family, religion, traditional forms, veneration of ancestors… As in Michael Crighton’s line about biology, “Life finds a way.” Small wonder that most post-communist or even late-communist countries begin to harbour these primal qualities in the end, against all odds.

Journalistic opinion pieces decrying Dublin’s urban decay, decry the surface of change only: the buildings and the nightlife. They do not concede the depths of change. Their contention is that an authentic Dublin is being lost, but lost to whom? To whom does Dublin belong? To whom does Ireland belong? What definition of “authentic” could even survive the nihilism of their basic outlook. These are people whose definitions of national belonging are so relativistic as to be inoperable except as barriers to a functioning nationality. Why should some hipster concoction of urban community be any more defensible? Do the cultural shock-troops of globalism really expect to inherit the earth? Or do they knowingly settle for the crumbs that are thrown their way? The culture war victories of same-sex marriage and abortion for example. Where is the affordable housing, the better pay and conditions, the liveable economy? We see the aspirations of progressive urbanism increasingly bundled with a language of catastrophe and broad transition; the language of crisis, climate, reset, collapse, debt, and that most costly of human upheavals (costly in human life): industrial revolution. The promise of economic benefits and broad distribution of wealth are increasingly hostage to a moment of historical rupture in which the activist Left hope to prosper, but in reality are simply being used.

End Times

The cogs in the machines are as jubilant in their “liberation” from the past as are the slave drivers. The individual today is not so much alienated from the products of their energies as from the human drive for life itself. Into all this comes the pageantry of apocalypse. The End is Nigh again. The desire to save the world from humanity or humanity from the world. But it is apocalypse as performance art, promoted as media spectacle, presented as a phoney war of young against old. Groups like Extinction Rebellion get bussed in to add emphasis to what is a top-down global agenda fully supported by finance capital. Time and time again we see the global finance big-picture dovetail with the left-wing culture war. “Climate anxiety” doubles as poetic realism for the dispossessed: a generation who cannot afford to have children, finding a moral reason not to have children. Fear of the future.

It is a post-national feeling, a post-natal feeling, a lazy nihilism perfectly equipped to an age of corporate oligarchy and vaunted “human obsolescence”. They inhabit the entire drafty world at once even as they return to their one bedroom apartments every evening. Their reality is global. The workforce in which they compete is global. The culture they consume is global. Their morality is global. But they expect there to be a cosy pub down the corner where everyone knows each other and where everyone helps each other out. They expect a safety blanket of identity and inter-generational trust to exist in a society sundered from the natural order.

Nothing is a better test of an ideology than the failure of its adherents at the moment of their greatest ascent. We see in cities across the western world, the same lame excuses. “The cultural sphere is progressive and cosmopolitan but the forces of business and finance are reactionary.” The implication being that the “failures” of modern society are insulated from the “successes” in some infinite Cold-War-like stand-off by which liberalism’s toxicity remains above suspicion. In reality, they are of the same malign source, in each case reaping what they have sown; hipsterish protest cults and hyper-capitalists lusting after a borderless, post-national world. Whether seeking to push the boundaries of moral decency or the boundaries of tax avoidance, the city landscapes look the same. And, in the end, all the cities look like all the other cities. None of them called home.

Nothing is a better test of an ideology than the failure of its adherents at the moment of their greatest ascent. We see in cities across the western world, the same lame excuses. “The cultural sphere is progressive and cosmopolitan but the forces of business and finance are reactionary.” The implication being that the “failures” of modern society are insulated from the “successes” in some infinite Cold-War-like stand-off by which liberalism’s toxicity remains above suspicion. In reality, they are of the same malign source, in each case reaping what they have sown; hipsterish protest cults and hyper-capitalists lusting after a borderless, post-national world. Whether seeking to push the boundaries of moral decency or the boundaries of tax avoidance, the city landscapes look the same. And, in the end, all the cities look like all the other cities. None of them called home.

This article was submitted by a National Party member. If you would like to submit an article for publication on the National Party website, follow this link.