People will say hard things about us now, but we shall be remembered by posterity and blessed by unborn generations.

An Intimate Conflict

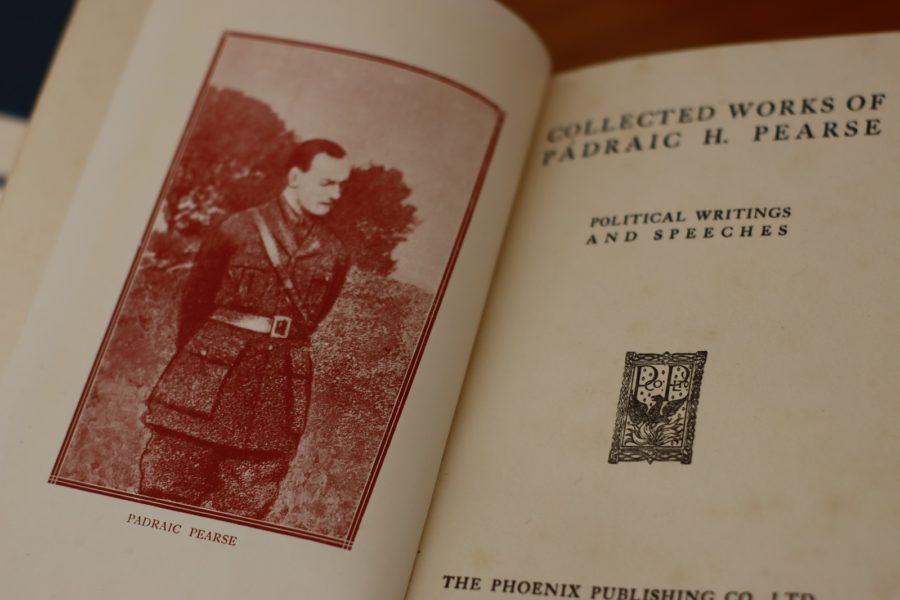

The confusions about Pearse begin with his name, or rather the many variations of his name. He signed his letters either in the English, Patrick Henry Pearse, or in the Irish, Pádraig Mac Piarais, but he is known to history mostly as Pádraig Pearse, the English and the Irish combined. In a way it gives expression to that tension of which he was most acutely aware and which was to dominate his whole life’s work. That is the conflict—physically and culturally—between separate peoples for dominance over one territory. In a way he contained this tension within himself on account of his father’s English blood.

He writes that when his father and mother married, “there came together two widely remote traditions—English and Gaelic.”

“And these two traditions worked in me, and, prised together by a certain fire proper to myself—but nursed of that fostering of which I have spoken—made me the strange thing that I am.” Strangely, this dynamic lives on in the name most people choose to remember him by.

The intimate conflict of cultures living alongside one another is apparent all through his work. As is his ultimate conclusion that one side, in the end, must overcome the other. And that that struggle is innate. It is human. As in our own day, we find ourselves not choosing struggle so much as being born into it. Louis Le Roux says of Pearse: “He understood that the clash between Ireland and England came from an antagonism of culture and race”, that is two cultures which were the product of two races, and that “in a free Ireland one of the two races must definitely establish its unquestioned supremacy. The Irish, the real Irish, authentic in race, language and tradition, wished that victory should go to themselves in that struggle, and to that end hoped and worked for the survival of Irish Nationality.” Writing in 1913, Pearse puts the situation starkly: “It is evident that there can be no peace between the body politic and a foreign substance that has intruded itself into its system: between them war only until the foreign substance is expelled or assimilated.”

In the same way, one might argue that the political system in Ireland post-1922 has never quite come to terms with Pearse. They tiptoe around him because he cannot be expunged from the record. He cannot be expelled outright. And yet he cannot be assimilated outright. He is too ultra-nationalistic. He is too ultra-radical. And unlike the radicality of Connolly which to some extent can be tamed, or has been tamed, Pearse seems to get more radical as the years pass. He seems to challenge the dominant political ideas of the last hundred years. He stands for primordial Gaelicism, heroic manhood, romantic nationalism and self-sacrifice, none of which really fits in with complacent mercantile liberalism.

In a prospectus for Scoil Éanna from 1910 we find statements like the following, written in Irish:

“Féaċtar le fonn do ċur orṫaa saoġal do ċaiṫeaṁ ag obair go díċeallaċ díograiseaċ ċum leasa a n-aṫarḋa nó, má ḃíonn gáḃaḋ leis ċoiḋċe, bás d’ḟáġáil ar a son.”

“It will be attempted to inculcate in the pupils the desire to spend their lives working hard and zealously for their fatherland and, if it should ever be necessary, to die for it.”

It is hard to imagine that being written in a secondary school prospectus today. Indeed, it would probably get the school closed down. Many of his pronouncements would, if made today, get him thrown out of “polite society”. The consensus makers in our time have no claim on him. They neither want to claim him nor have any right to do so. The only motive they have in claiming him is the power to neutralise his legacy.

He was not like them. He did not think as they do. He pursued the claim to national belonging and believed in it to the death. He embodied a nobility of mind and spirit that placed him beyond the grasp of reductive materialism. This is a man who lived his life in the knowledge and anticipation of supreme sacrifice, his whole mind focused towards that final expression of conviction: “To the deed that I see, And the death I shall die.”

He lived his life in negation of everything that our current society stands for. Other rebels have been domesticated but Pearse, despite everything, has not been. As central as he is to the whole mythology of the Irish State, he is viewed as an increasingly ambivalent figure. When the rebels chose Easter to stage their rising, they knowingly evoked the death and resurrection of Christ. There is a famous story by Fyodor Dostoevsky in which Christ returns only to be condemned by the Church authorities and burnt at the stake. One can easily imagine that Pearse, arriving back in Ireland, would be met by a similar state inquisition.

When one reads the infamous Irish Times editorial of 1 May 1916, one does not feel the attitudes on display are very much removed from how nationalism is viewed in our own day. “The State has struck, but its work has not finished. The surgeon’s knife has been put to the corruption in the body of Ireland, and its course must not be stayed until the whole malignant growth is removed.”

It is like a perverse echo of Pearse’s own words, twisted by the enemy and directed against him. In a way this same editorial could be issued today as a final condemnation of Pearse’s legacy. They have done so much to marginalise, distort and pervert his memory. The killing blow has yet to be dealt to the cause he represents, but they are certainly calling for it.

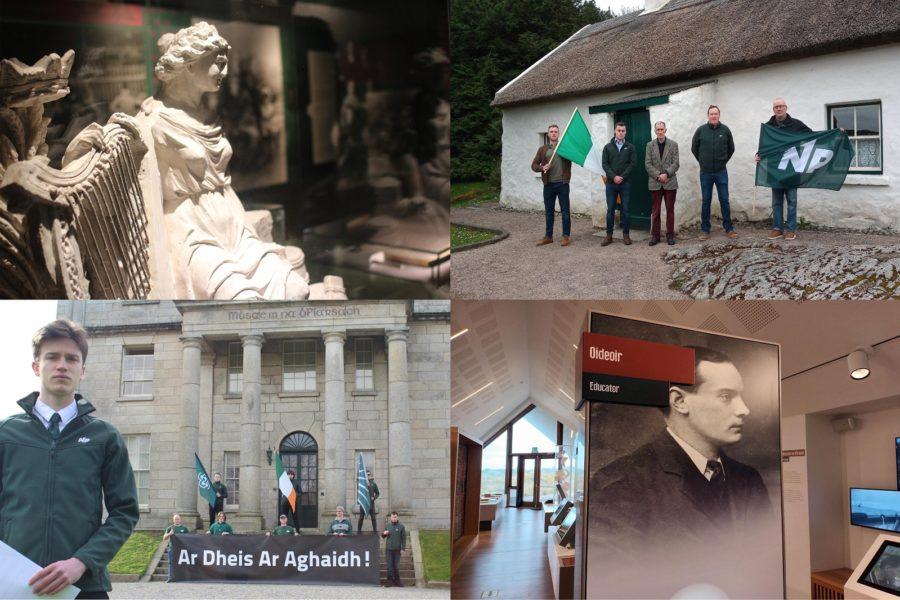

There is no place in a petty, mercantile society for a hero like Pearse. He has in effect become the foreign substance. And as Irish nationalists we share in his exclusion. The exclusion of Pearse is the exclusion of nationalism. As nationalists, we feel the whole apparatus of modern Ireland is at war with us, determined to expel us or assimilate us. And as we take stock in April 2022, reflecting once again on the Rising of 1916, it is partly to affirm that we are still here. The things that Pearse stood for still matter. The conflict for the soul of Ireland continues. We continue. Ireland continues.

Pearse and the Modern World

If one were to criticise the state which emerged 100 years ago, out of the tumultuous events of 1916 to 1922, the phrase “half measures” would crop up again and again. The Civil War politics of Ireland, that broken marriage of good intentions, gave birth to a society that never quite went far enough with anything that it did right. Pearse was not a man for half-measures, though he was not unreasonable, and you feel that the thing he would criticise most today would be the state of the Irish language, which not only has not gained parity with spoken English but is being overtaken by new foreign languages.

Pearse would often be critical of the Gaelic League of which he was a part, seeing it as too much a limited urban fad or as too moderate .“More rebels” and “fewer grammaticists” was his comment. He saw the need for bilingual education (instructed in Irish) and more dynamic, more expansionist Gaeltact areas, hotbeds of ideas, recolonising the rest of Ireland, rather than being zoos of study for cosmopolitan linguists. The situation today speaks for itself in so far as it falls short of his hopes in those days of the Gaelic League. The modern world has little interest in reviving Gaelic civilisation.

Pearse’s attitude to industrial modernity was at best ambivalent. Another reason why he is not in fashion. The nationalism he strove for was of an “old tradition” and much of life’s answers, came it seemed to him out of the past, out of received wisdom and inherited tradition. His philosophy of history at times seems cyclical and traditionalist, radically at odds with the secular religion of progress. He writes:

“… in some directions we have progressed not at all, or we have progressed in a circle; perhaps, indeed, all progress on this planet, and on every planet, is in a circle, just as every line you draw on a globe is a circle or part of one. Modern speculation is often a mere groping where ancient men saw clearly. All the problems with which we strive (I mean all the really important problems) were long ago solved by our ancestors, only their solutions have been forgotten.”

One of his heroes, John Mitchel also had a healthy disregard for the gods of progress: “It is altogether a new thing in the history of mankind, this triumphant glorification of a current century…no former age, before Christ or after, ever took pride in itself and sneered at the wisdom of its ancestors; and the new phenomenon indicates, I believe, not higher wisdom but deeper stupidity.”

This tragic outlook is something that radically differentiates Pearse and Mitchel from progressive and utopian thinkers. It is what makes them so difficult to assimilate. Like many Irish nationalists of his time, Pearse was appalled by the mercantilism and materialism that seemed to Gaelic Leaguers to embody the English spirit. Napoleon had called the English a nation of shopkeepers, and the Irish made a philosophy out of it. All the wealth and power of the British Empire was not worth the sad decline of human spirit under industrial conditions.

“It is no doubt a glorious thing to rule over many subject peoples, to dictate laws to far-off countries, to receive every day cargoes of rich merchandise from every clime beneath the sun; but if to do these things we must become a soulless, unintellectual, Godless race—and it seems that one is the natural and necessary consequence of the other—then let us have none of them.”

Mere Nationalism

It must also be noted that Pearse’s sympathy for the Irish people extended to the “millions that toil and sweat”. The workers in the factories and mines and ports and so on. By embracing the work of James Fintan Lalor and supporting the 1913 strikers, Pearse helped to bring James Connolly fully on board with the “mere nationalists”. “Mere nationalist” was a derogatory phrase used by some socialists. Another variation was “bourgeois nationalist”, still essentially the slur thrown around today by mere socialists who have sold out the Irish-of-no-property for the foreigner-of-no-property. That of course is an occupational hazard of internationalism, something Pearse and most nationalists of the time were highly suspicious of.

The key to nationalism, always, is a strong cross-section of working and middle class people, if we can use those terms in an Irish context, spearheaded by a vanguard. From that you carry the nation. The limitation of mere socialism, locked as it is to economic determinism, is its sectionalism. In Ireland now they have thrown aside the native working class for new sections of society, i.e. foreigners and assorted lifestyle-minorities. James Connolly would tear shreds out of the socialists of today for their complicity in the large scale importing of foreign labour, among other things. Much the same way as he tore shreds out of certain of his own contemporaries like William Walker.

Connolly is one of the great Irish polemicists, and much as his work is grounded in economic determinism, some of which has later proved to be a cul-de-sac, his talent is that he transcends that. And there is probably no greater example of the overcoming of sectionalist thought than Connolly’s supreme gesture in 1916. It is said that on the morning of the Rising he told his men that there was no longer a Citizen’s Army or an Irish Volunteers, there was only the Army of the Irish Republic. In prison he mused that the socialists “will not understand why I am here. They forget I am an Irishman.” They still do not understand. And certainly do not understand Pearse. Anymore than they understand you or I.

Pearse unlike Connolly was not in any way an economic determinist, seeing himself not as a communist or a syndicalist but “old fashioned enough to be a Catholic and a nationalist.” His great empathy for the ordinary Irish people, and his ability to express that in plays, speeches and pamphlets, helped to bridge the gap between social justice and heroic nationalism.

Desmond Ryan described Connolly as the “most terrific expression in a personality of the modern revolutionary spirit” and described Pearse as “the grandest incarnation in men of Irish blood, of the ancient tradition of Irish nationhood.” Le Roux describes their meeting of minds as follows:

“The national revolution will not be complete without a social revolution,” says Pearse. “Social revolution will not have the desired results without a national revolution,” says Connolly. From the beginning of 1914 onward, Pearse and Connolly understood each other, and the day was to come when the two patriots came together to proclaim a Republic and die bravely for the whole nation, the proletariat included.

It was not a sectionalist rising, which would have been fatal. It was not a revolution merely to change men’s material conditions, but to uplift their intellect and soul, and their material conditions into the bargain.

Closing Remarks

There is not much else to be said here about Pearse. Much has been said about him, good and bad. Much has been said that is hideous slander. Almost everything libelous that has been said about Pearse is a deliberate misunderstanding of simplicity. “In his youth,” Desmond Ryan writes, “Pearse is said to have been a dreamer, above all a student, rarely playing games and lost in his books.” The memoirs later compiled by his family, conforms with this, and nothing more really is necessary to explain his personality. He was the opposite of Connolly’s gregarious, outgoing spirit. He was typical of the introvert who dares to be a man of action. And as always, is misunderstood.

His goals in life, again summed up by Desmond Ryan, were to “edit a bilingual paper, to found a bilingual secondary school and to start a revolution.” He accomplished all that and more, producing a strong literary outpouring of poems, stories and plays in two languages, all of which are much neglected now in the Ireland he helped bring into existence.

His words at his Court Martial stand for themselves as a testament to everything he was and stood for. And a repudiation of everything our current society is and stands for. It is a contract between the generations written not in ink but in blood.

When I was a child of ten I went down on my bare knees by my bedside one night and promised God that I should devote my life to an effort to free my country. I have kept that promise. As a boy and as a man I have worked for Irish freedom, first among all earthly things. I have helped to organise, to arm, to train, and to discipline my fellow-countrymen to the sole end that, when the time came, they might fight for Irish freedom. The time, as it seemed to me, did come, and we went into the fight. I am glad we did. We seem to have lost. We have not lost. To refuse to fight would have been to lose; to fight is to win. We have kept faith with the past, and handed on a tradition to the future.

This article was submitted by a National Party member. If you would like to submit an article for publication on the National Party website, follow this link.