This is the first in a series of articles on the phenomenon of mass-immigration in Ireland since the 1990s. They will focus on presenting a general chronology of events, a presentation of the demographic effects and a look at the consequences for Irish nationality, particularly in the area of citizenship.

In this first article we will focus on the period from 1998 to 2008, the period which encompassed the Celtic Tiger and the demographic, cultural and economic transformation of Irish society, ending finally in catastrophe. The focus here will be primarily on economic migration. As such it is a story dominated by money and by the need to justify greater growth and greater “prosperity”.

Migration Policy Institute (Above)

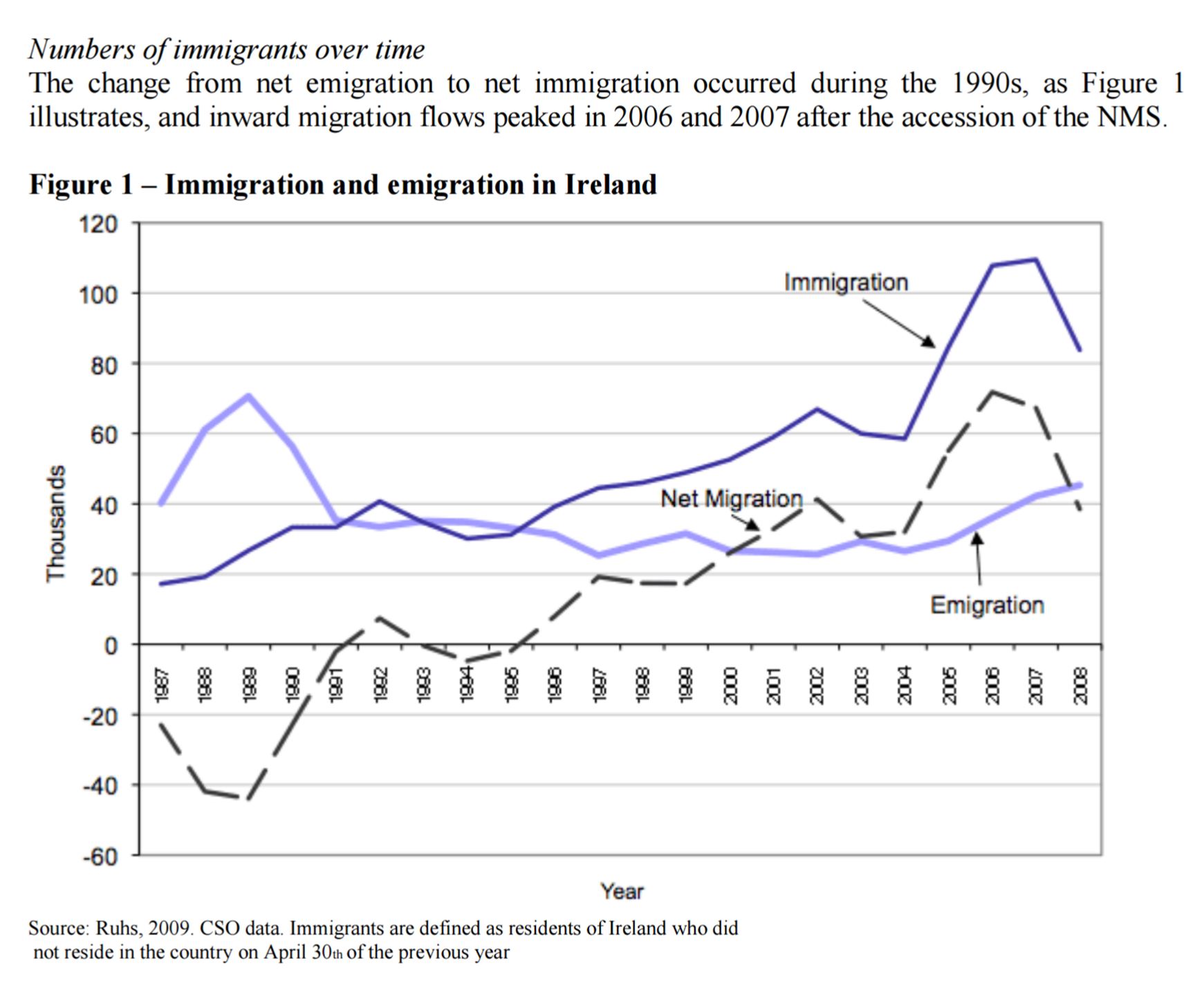

Writing in 2009 Ruhs and Quinn characterise immigration into Ireland in five broad phases.

- Generally net emigration prior to the early 1990s.

- Increasing immigration from the mid-1990s to early 2000s, driven by returning Irish nationals. There were also dramatic increases in the number of asylum applicants.

- New peaks in non-EU immigration flows and in numbers of asylum applications from 2001 to 2004.

- A shift from non-EU immigration flows to EU flows after EU enlargement (2004 to 2007). The high levels of immigration from the new EU Member States brought immigration to unprecedented levels.

- Reduced but still significant net immigration in 2007-2009, the fall largely resulting from decreased flows from new EU Member States.[1]

They view 1996 as the initial turning point, the year in which Ireland became the last EU country to experience net immigration.

“The main reason: rapid economic growth created an unprecedented demand for labor across a wide range of sectors, including construction, financial, information technology, and health care. Unemployment declined from 15.9 percent in 1993 to a historic low of 3.6 percent in 2001.”[2]

The economic development of the 1990s led to a surge of migration into the twenty-six counties, much of it driven by returning Irish nationals. The period from 2000-2004 saw a significant rise in immigrants from outside the European Union. This led to the citizenship referendum. The numbers of returning Irish nationals peaked in 2002 at 27,000, but “their relative share in total immigration fell from about 65 percent in the late 1980s to 44 percent from 2000 to 2002.”[3] EU enlargement led to a new phase of large scale Eastern European immigration. From 2002 to 2007 the number of returning Irish nationals fell as a percentage of total immigration to 20,000 or 18%.[4]

The shift in Ireland’s demographic trajectory is nothing if not extreme. Indeed, the relative poverty of where we were coming from may well have exacerbated the need in Irish public life to justify prosperity at any cost.

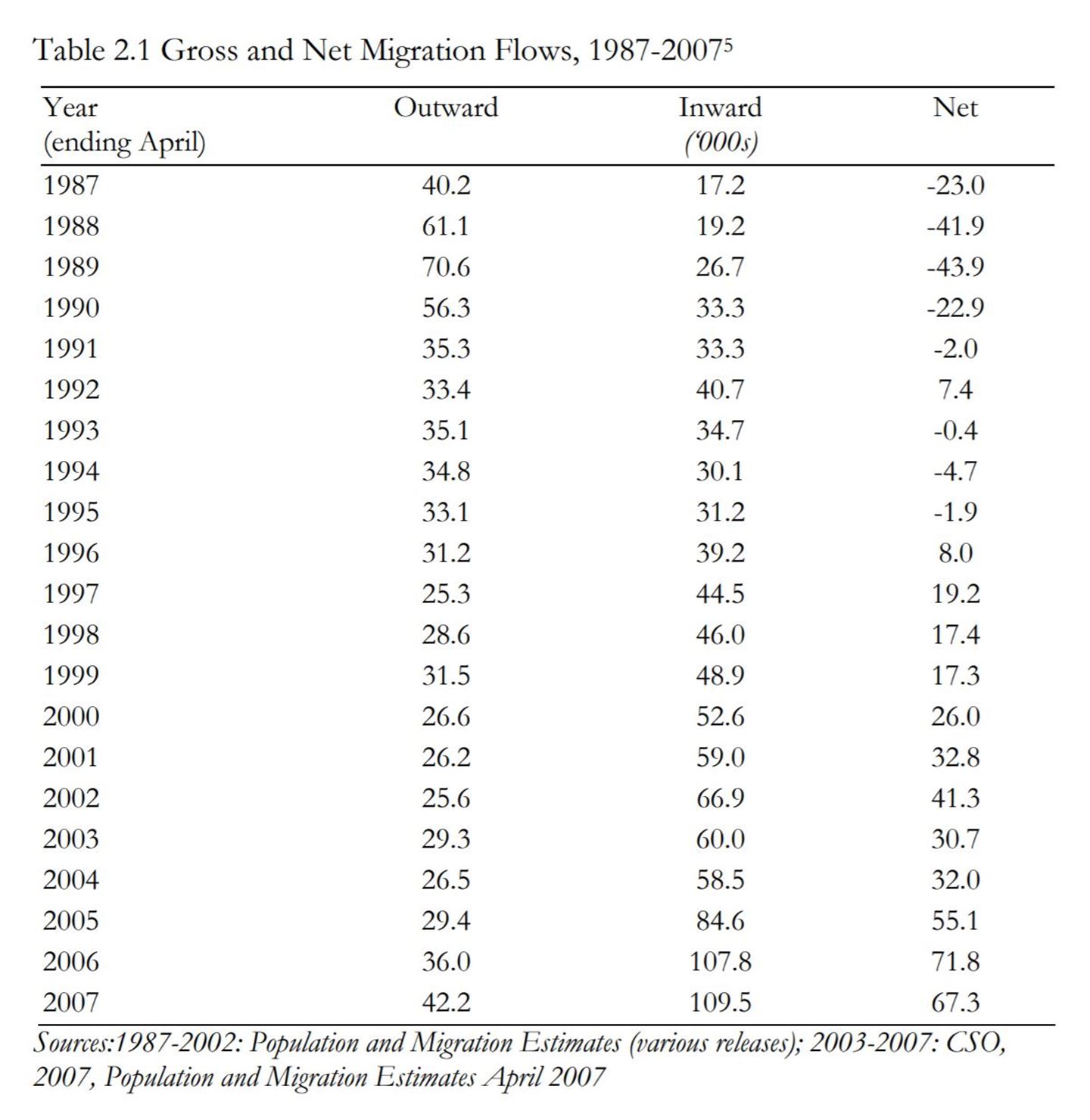

“There were substantial population losses due to emigration in the late 1980s: the annual outflow peaked at over 70,000 in 1989. However the position stabilised in the early 1990s when the migration inflows and outflows were more or less in balance. Inward migration has grown steadily since the mid-1990s, to well over 100,000 per annum in the last two years, and peaking at almost 110,000 in the twelve months to April 2007.”[5]

The following diagram published by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) in 2008 demonstrates the extraordinary transition which occurred in that twenty year period.

Throughout this period Ireland experienced massive economic growth and immigration became but one more component associated with a changing new Ireland, freed at last from the shackles of austerity and emigration. There was no attempt by any major political party to curb immigration or to draw attention to the long term consequences it might have on Ireland, whether cultural, social or otherwise. The failure was particularly notable among Irish Republicans who might have been expected to take a more nationalist view of the situation. At their 1998 Ard Fheis, Sinn Féin in fact passed a motion stating that they would work “for the achievement of the optimum position of no restriction on immigration into Ireland.” The motion passed unanimously.[6] While the complicity of the parties in power is easy to explain, connected as it was to their drive for economic growth at any cost, the complicity of opposition parties is more perplexing.

Throughout this period Ireland experienced massive economic growth and immigration became but one more component associated with a changing new Ireland, freed at last from the shackles of austerity and emigration. There was no attempt by any major political party to curb immigration or to draw attention to the long term consequences it might have on Ireland, whether cultural, social or otherwise. The failure was particularly notable among Irish Republicans who might have been expected to take a more nationalist view of the situation. At their 1998 Ard Fheis, Sinn Féin in fact passed a motion stating that they would work “for the achievement of the optimum position of no restriction on immigration into Ireland.” The motion passed unanimously.[6] While the complicity of the parties in power is easy to explain, connected as it was to their drive for economic growth at any cost, the complicity of opposition parties is more perplexing.

It was clear to anybody who was prepared to look that Ireland was heading down a road that other countries had thread before. In 1998 columnist Kevin Myers gave a timely warning:

“We can listen and we can learn from the experiences of others. We must have controls over immigration… And we should certainly not expect the least advantaged and least educated communities in Dublin and elsewhere to be the sole unassisted hosts of ghettos and newcomers. Down the road lies certain disaster.”[7]

Then as now, such views were dismissed as populist and reactionary. “Down the road” we were going to go. In the space of a decade Ireland would experience one of the most extreme demographic transformations in history, transitioning from a “homogeneous Catholic society to an ethnically, racially and religiously diverse society.”[8]

“Furthermore, in contrast to many other European states partly because of Ireland’s role as a colony rather than a coloniser, immigrants in Ireland came from an enormous variety of countries and they settled all over the country and not just in Irish cities.”[9]

Indeed, nowhere in Ireland was to be left untouched, from the smallest village to the most remote coastal island.

The Nice Treaty and the Citizenship Referendum

In June 2001 a determined group of No campaigners drawn from across the political spectrum including ‘No to Nice’ (drawn largely from the pro-life movement), the Green Party, Sinn Féin, the Irish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Justice and Anti-poverty Body Action from Ireland (AFRI), the Peace and Neutrality Alliance, the National Platform, and Christian Solidarity had convinced the Irish electorate to vote No to the ratification of a European treaty, sparking chaos in European politics. Next time around the guns were out from the establishment parties. Immigration became a focus of the confrontation.

In October of 2002 in the leading up to the second treaty vote, an Irish Times editorial warned that a “dangerous surge of racism and xenophobia has accompanied Ireland’s recent economic boom and the resulting opening up of Irish society to a level of immigration it has not experienced before.”[10] This was in direct response to elements within the No campaign.

“The organisation [No to Nice] argues that the Government’s decision not to seek a derogation from the free movement of labour clauses in the accession treaties means Ireland will become liable to a huge surge of immigration when these countries join the European Union.”[11]

The focus of the controversy was the government’s decision to “give 75 million Eastern Europeans the right to live and work in Ireland.”[12] If the Nice Treaty were to pass then this open borders policy with countries such as Poland would come into effect from January 2004.[13]

Justin Barrett of the No to Nice group promised to make immigration a key issue of the campaign stating “If it is not to the fore in people’s minds now, it will be by the end.”[14] He claimed that The Irish Business and Employers’ Confederation was preparing to use foreign labour as “a battering ram” to lower pay for Irish workers.[15]

Minister for Foreign Affairs Dick Roche vigorously rebuffed the claims of Anti-Nice campaigners that EU enlargement would lead to large scale immigration, stating in a heated exchange of statements with Antony Coughlin of the National Platform that “existing surveys on migration patterns in Europe show that the claims are false. Ireland barely registers as a location in these surveys.”[16] He also stated in September 2002 that there was “no credible reason” why such enlargement would be “accompanied by large movements of people. All the evidence points in the opposite direction.”

Proinsias de Rossa MEP, in a letter to The Irish Times in July 2002 cited a European Commission paper published in March of that year which suggested that 76% of Eastern European migration “will go to Germany and Austria. So, even if we take the higher estimate of 150,000 workers migrating each year to the EU15, Ireland will be host to a tiny fraction of these, probably not more than 2000.”[17]

The second time around Ireland voted Yes and come 2004 Ireland did indeed permit unrestricted migration from the ten accession countries of Eastern Europe. As a result the period 2004 to 2007 was the peak, when Ireland was receiving well over 100,000 immigrants per year. It should be noted that already even in 2004, the number of non-Irish nationals in the labour force was higher than in most other EU countries (OECD, 2004).

Ironically, 2004 was also the year in which Ireland made its strongest stand against mass-immigration. In that year a referendum was held to amend the constitution in relation to birth-right citizenship. According to this change, a child born to non-Irish parents was not automatically granted citizenship unless one of the parents had resided lawfully in the country for three out of the previous five years.

“The move comes after several years of Government concern over the growing number of foreign women presenting late in their pregnancies to give birth in Ireland, and after the masters of the four Dublin maternity hospitals asked the Minister to deal with the problem.”[18]

At the time Aengus Ó Snodaigh of Sinn Féin accused the Minister for Justice Michael McDowell of “quite deliberately setting about making race an election issue”.[19]

In the run up to this referendum Ronit Lentin, director of the MPhil in Race, Ethnicity, Conflict, Department of Sociology and founder member of the Trinity Immigration Initiative, Trinity College, Dublin, wrote an article entitled ‘From racial state to racist state: Ireland on the eve of the citizenship referendum’. In it she wrote: “Instead of a language of ‘integration’ and ‘interculturalism’, I propose an interrogation of how the Irish nation can become other than white (Christian and settled), by privileging the voices of the racialised and subverting state immigration but also integration policies.”[20] It was something of a foreshadowing of the type of discourse which would in the following decade come to dominate the Irish public sphere.

The referendum passed by a landslide on the 11th of June 2004 but its effects were somewhat nullified by the Irish Born Child 2005 Scheme which allowed non-Irish parents of Irish born children to remain in Ireland for two years, and subsequently apply for renewal of permission. A successful renewal allowed applicants to remain in Ireland for up to three years, after which they were eligible to apply for Irish citizenship.

Almost 18,000 applications were submitted under the scheme, and of these, almost 16,700 were approved. During 2007, the government made arrangements to process applications for renewal; 14,117 renewals had been granted by the end of 2008.[21]

In retrospect, 2004 is a crucial year. The reaction of Liberal Ireland to the Citizenship Referendum was one of horror and distaste. It represented what Bryan Fanning and David Farrell in The Irish Times later refer to as an “exclusionary” concept of national identity.

“The 2004 Citizenship Referendum seemed to defensively define Irishness; almost 80 per cent of voters supported removing citizenship at birth to the Irish-born children of immigrants. The outcome of the Referendum indicated that nationalism still mattered hugely.”[22]

In 2004 Justin Barrett ran in the European Elections on an Anti-Immigration platform under the slogan “Putting Irish People First.” He claimed that government policy on immigration was being set by the neoliberal Progressive Democrats. The PDs were in his words “wagging the tale” of Fianna Fáil on the issue and that “incentives for immigrants to come here are putting lives at risk. Pregnant immigrants are presenting in Irish hospitals at the last possible moment without medical histories.”[23]

Peak Immigration

From 2004 onwards a new wave of economic migration hit and its effects, coming at the height of Celtic Tiger frenzy, were to totally transform the country.

“… in 2004, in what turned out to be a radical act of social engineering, Ireland became one of just three countries that did not impose any restrictions upon the free movement of migrants from the new east European EU member states. According to the 2016 census some 17 per cent of the population of the Republic of Ireland were born abroad.”[24]

In the same article Fanning and Farrell allude to the rationale employed to justify mass-immigration post-2004. The tactic used by State institutions and by big business was to emphasise the “economic benefits” and to ignore everything else. Integration of immigrants basically became “defined as participation in the labour market.” “For example, Managing Migration, a 2006 report by the National Economic and Social Council credited the persistence of economic growth to ongoing immigration.”[25] This seems to fit in with the late Brian Lenihan’s assessment (in an interview with Matt Cooper in 2009) that it was “cheap credit from the European Central Bank” and “the availability of cheap labour after 2004” that were the key factors in overheating the Irish economy.

The National Party summarised the relationship as thus:

“In 2001 our commitment to join the single currency area became a fact, and two years’ later there was the accession to the EU of the bulk of Eastern Europe and with it an endless supply of cheap and not always unskilled labour. After a brief flirtation with recession in 2000 the economy took off again. But to the watchful, there was something different about the second “half” of the boom. It wasn’t based on new markets, and brought almost no new factories. It was the evasion of recession by cheap money of an artificially low interest rate by the ECB, wages stopped rising and there was a huge influx of immigrants into the labour market. And cheap money went where cheap money goes when there’s nothing real to invest in, into speculation and in particular property speculation.”[26]

The significance of Eastern European immigration can be glimpsed in a 2008 report by the ESRI in which they state that “Irish government labour migration policy was to “meet Ireland’s labour needs from inside the enlarged EU.”

“Even before the accession of ten new EU Member States in May 2004 the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment favoured work permit applications made on behalf of nationals of these ten countries.”[27]

Immigration from non-EEA countries actually fell somewhat in the years from 2003 – 2007, reflecting “Irish policy of seeking to meet labour needs from within the enlarged EU.” The figure fell from 25,000 in 2003 to 21,000 in 2007.[28]

The impact of immigration from the accession countries cannot be underestimated. In Britain its consequences are now widely recognised, with some even seeing it as a key contributor to the eventual Brexit vote in 2016, allowing as it did the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) to build a eurosceptic platform out of immigration control. In 2013, Labour MP Jack Straw conceded that the policy of throwing open the doors in 2004 was a “spectacular mistake.”[29] It is a mistake Irish politicians have been less willing to concede.

The scale of demographic change could not be ignored completely. Prof. Ferdinand von Prondzynski stated in 2005 that the native Irish population faced the likelihood of becoming a minority ethnic group in Ireland by the middle of the century.[30] The report received some media coverage at the time, but no serious debate occurred. Again Prondzynski emphasised the economic benefits of immigration. In order for Ireland to “remain prosperous” he stated, sustained levels of mass-immigration were necessary. In short, it was necessary for the good of the country that Irish people become an ethnic minority in Ireland. Everything could be justified on the basis of continued prosperity.

The economics of immigration did not however always tally with everyone’s definition of prosperity. In 2006 Pat Rabbitte, then leader of the Labour Party, was accused of stoking anti-immigrant fears when he spoke about the displacement of Irish workers in industries such as “hospitality, building and the meat factory sectors where he says non-national workers are replacing Irish workers at lower wages.”[31] This was related to “a number of high profile cases, notably those involving the companies GAMA and Irish Ferries, which suggested that Irish workers were being displaced by cheaper labour from abroad.”[32] This led to the creation of a new National Employment Rights Authority.

In late 2006 CSO director Bill Keating presented labour figures which suggested that there were now “350,000 foreigners living in Ireland” which was 25% higher than “show up in surveys by the Central Statistics Office.” Supposedly due to a lower response rate among non-nationals. This was at a time when labour force figures were up 83,500 from the previous year and it was estimated that half the new jobs went to immigrants.[33] From 2004 to 2007 “well over half the total employment growth” was accounted for by non-nationals.[34]

The official CSO statistics for 2006 showed the Irish population had grown by 8.1% in the four years since 2002. The average rate per year was 2% which was the highest on record. The 2006 population had not been exceeded since the census of 1861. 131,000 of this was attributed to natural increase while the remaining 186,000 was attributed to net immigration.[35]

In 2007 the CSO office in its revised population and migration estimates for 2002-2006 stated that Ireland continued to have the fastest growing population of any EU country, and stated that “The April 2006 to April 2007 increase of 2.5 per cent represents the third year in a row in which an annual population increase of over 2 per cent was recorded.”[36]

In September 2009, the ESRI stated that the number of immigrants who had settled in Ireland over the previous ten years was without precedent in the Western world. It was stated that by 2007, Eastern Europeans made up “over 4pc of the population” having been “a negligible percentage of the population five years earlier.”[37] To put this in perspective the immigrant population of the United Kingdom rose by only 2% “in the 30 years after 1960.” The number of Eastern Europeans in Ireland had grown from about 10,000 in 2002 to 200,000 in 2007. Dr. Alan Barrett of the ESRI was reported as saying that the inflow of foreigners had kept wages down and that wages “would be 7.8pc higher due to labour shortages if we had not accepted Eastern Europeans”.[38]

Lower wages are presented of course as a resounding economic good. As John Fitzgerald puts it in The Irish Times “Research shows that this influx of skills improved our competitiveness by putting downward pressure on wage rates for the best paid, and allowed the economy to grow more rapidly, helping to solve the unemployment problem.”[39]

Meanwhile the cultural impact of mass-immigration was more and more acute. When the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) published its third report on Ireland in 2007 it “welcomed the National Action Plan Against Racism (NPAR) established in 2005 and also praised the removal of the “requirement for competency in the Irish language for entry to An Garda Síochána”.[40] The latter was highly significant in a society where Polish was soon to overtake Irish as the second most spoken language.

On the 28th of September 2007 Kevin Myers appeared on The Late Late Show in what he later described as an attempt to create a national debate on the issue of immigration. The hour was late however and no such debate ensued. In actual fact, and Myers alluded to it in the course of his interview with Pat Kenny, events were in motion that would soon put a close to this particular chapter in migration history. The global financial system was rumbling towards catastrophe, Ireland to be one of its chief victims. A year later on September 15th 2008, Lehman Brothers collapsed.

The economy imploded in 2008 but by then mass-immigration had had an unimaginable long term impact on the country. In the midst of a collapsing economy, Irish people were in no condition to assess just exactly what had happened demographically or culturally. Immigration seemed for a period irrelevant. And the narrative for the next few years was of non-nationals leaving Ireland and going home. Meanwhile, as they had done time and time again throughout our history, the Irish began to leave this country and seek employment overseas. But unlike previous occasions, there were foreigners here to take their places who would soon be bonafide Irish citizens and as far as our State institutions were concerned, more Irish than the Irish themselves.

This article was submitted by a National Party member. If you would like to submit an article for publication on the National Party website, follow this link.

REFERENCES

[1] Ruhs, Martin and Quinn, Emma, ‘Ireland: From Rapid Immigration to Recession’ Migration Policy Institute (September 2009) – http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/ireland-rapid-immigration-recession

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Quinn, Emma and Stanley, John and Joyce, Corona and O’Connell, Philip J., ‘Handbook on Immigration and Asylum in Ireland’ Research Series No.5, The Economic and Social Research Institute (October 2008) p.8 – https://www.esri.ie/pubs/RS005.pdf

[5] Ibid.

[6] ‘Undocumented Migrants: Immigration Control Platform’ Joint Committee on Justice, Defence and Equality Debate (April 2015) – http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring/DebatesWebPack.nsf/committeetakes/JUJ2015040100002

[7] Myers, Kevin, ‘An Irishman’s Diary’, The Irish Times, (30/01/1998) – https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/an-irishman-s-diary-1.178330

[8] Glynn, Irial, ‘Can Ireland’s emigration past inform the incorporation of its immigrants in the future?’ (translation: Glynn I.A.), Chimera 26: 4-12. (2013) –http://research.ucc.ie/journals/chimera/2013/00/glynn/02/en

[9] Ibid.

[10] ‘Immigration and the Nice Treaty’ The Irish Times (22/08/2002) – https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/immigration-and-the-nice-treaty-1.1092833

[11] Ibid.

[12] Brophy, Karl, ‘Minister Deferends post-Nice Treaty “open doors” policy’ The Irish Times (09/08/2002) – https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/minister-defends-postnice-treaty-open-door-policy-26037273.html

[13] Ibid.

[14]Hennessy, Mark, ‘ No to Nice group criticises “reckless” freedom to work offer’ The Irish Times (22/08/2002) – https://www.irishtimes.com/news/no-to-nice-group-criticises-reckless-freedom-to-work-offer-1.1091076

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] De Rossa, Proinsias, ‘Debate on the Nice Treaty’ Letters Section of The Irish Times (13/ 07/2002) – https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/letters/debate-on-the-nice-treaty-1.1088489

[18] ‘Referendum to be held to restrict citizenship rights’ The Irish Times (11/03/2004) – https://www.irishtimes.com/news/referendum-to-be-held-to-restrict-citizenship-rights-1.1134950

[19] Ibid.

[20] Lentin, Ronit, ‘From racial state to racist state: Ireland on the eve of the citizenship referendum’ Variant: Issue 20 – (2004) http://www.variant.org.uk/20texts/raciststate.html

[21] Ruhs, Martin and Quinn, Emma, ‘Ireland: From Rapid Immigration to Recession’ Migration Policy Institute (September 2009) – http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/ireland-rapid-immigration-recession

[22] Fanning, Byran and Farrell, David, ‘Ireland cannot be complacent about populism’ The Irish Times (17/08/2018) –https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/ireland-cannot-be-complacent-about-populism-1.3598461

[23] ‘IRA man defects from SF to Euro hopeful Barrett’ The Irish Times (23/05/2004) – https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/ira-man-defects-from-sf-to-euro-hopeful-barrett-26220993.html

[24] Fanning, Byran and Farrell, David, ‘Ireland cannot be complacent about populism’ The Irish Times (17/08/2018) –https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/ireland-cannot-be-complacent-about-populism-1.3598461

[25] Ibid.

[26] ‘Interposition and Nullification’ The National Party (08/09/2018) – https://www.nationalparty.ie/interposition-and-nullification-part-two-descent-into-chaos/?preview=true

[27] Quinn, Emma and Stanley, John and Joyce, Corona and O’Connell, Philip J., ‘Handbook on Immigration and Asylum in Ireland’ Research Series No.5, The Economic and Social Research Institute (October 2008) p.10 – https://www.esri.ie/pubs/RS005.pdf

[28] O’Connell, Philip J. and Joyce, Corona and Finn, Mairéad, ‘International Migration in Ireland, 2011’ ESRI: Working Paper No 434 (May 2012) p.2 – https://www.esri.ie/pubs/WP434.pdf

[29] ‘Jack Straw regrets opening door to Eastern Europe migrants’ BBC News (13/11/2013) –https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-24924219

[30] Downes, John, ‘Irish could be minority ethnic group here by 2050’, Irish Independent (19/03/2005) – http://www.irishtimes.com/news/irish-could-be-minority-ethnic-group-here-by-2050-professor-1.424517

[31] O’Malley, Joseph, ‘Immigration on election agenda after Rabbitte taps into politics of fear’ The Irish Times (22/01/2006) – https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/immigration-on-election-agenda-after-rabbitte-taps-into-politics-of-fear-26407551.html

[32] Quinn, Emma and Stanley, John and Joyce, Corona and O’Connell, Philip J., ‘Handbook on Immigration and Asylum in Ireland’ Research Series No.5, The Economic and Social Research Institute (October 2008) p.24 – https://www.esri.ie/pubs/RS005.pdf

[33] Keenan, Brendan ‘Up to 350,000 non-Irish here – 25pc about CSO figures’ The Irish Independent (01/12/2006) – https://www.pressreader.com/ireland/irish-independent/20061201/282329675447212

[34] Quinn, Emma and Stanley, John and Joyce, Corona and O’Connell, Philip J., ‘Handbook on Immigration and Asylum in Ireland’ Research Series No.5, The Economic and Social Research Institute (October 2008) p.19 – https://www.esri.ie/pubs/RS005.pdf

[35] ‘Record Growth in Population’ Census 2016: General Report (July 2016) – https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/documents/2006PreliminaryReport.pdf

[36] ‘Population And Migration Estimates, April 2007, Foreign Nationals: PPSN Allocations And Employment, 2002-2006’ Central Statistics Office (April 2007) – https://www.cso.ie/en/csolatestnews/pressreleases/2007pressreleases/populationandmigrationestimatesapril2007foreignnationalsppsnallocationsandemployment2002-2006/

[37] Molloy, Thomas, ‘Influx of immigrants is “without precedent”’ The Irish Times (4/09/2009) – https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/influx-of-immigrants-is-without-precedent-26563538.html

[38] Ibid.

[39] FitzGerald, John, ‘We need to build on Ireland’s migration success story’ The Irish Times (04/05/2018) – https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/we-need-to-build-on-ireland-s-migration-success-story-1.3483281

[40] Quinn, Emma and Stanley, John and Joyce, Corona and O’Connell, Philip J., ‘Handbook on Immigration and Asylum in Ireland’ Research Series No.5, The Economic and Social Research Institute (October 2008) p.28-29 – https://www.esri.ie/pubs/RS005.pdf