On 6 June 2022 David Quinn, the former editor of The Irish Catholic newspaper and a regular conservative columnist in the mainstream press, tweeted “Unfortunately, I won’t live to see it, but I look forward to a day when Ireland is visibly more religious again thanks to immigration.” The response from the political right was swift and roundly criticised Quinn, holding him up as an example of all that is wrong with mainstream Irish conservatism.

At first glance, it appears Quinn was welcoming mass-immigration into Ireland for the simple reason that the importation of immigrants, mostly from the third world, would be of an older and a more traditional and conservative dispensation. As they gradually supplant the native population, the upside of this demographic transformation would be a more ‘religious’ populace. However, Quinn himself waxed lyrical in a column in the Sunday Times of 29 May that “Choosing who to welcome here is not racist.” This received scorn from the left, with many twitter liberals dogpiling on Quinn to point out the article’s premise was an oxymoron. A similar incident happened when Quinn penned an identical milk-livered column in 2017 entitled “It’s not racist to have fears over immigration.”

With that knowledge of Quinn’s recent efforts to dip his toe into the whirlpool of anti-immigration punditry, his tweet of 6 June may indicate a stoic-like acceptance of the realities of mass-immigration. Similar to his counterpart in England, Peter Hitchens, Quinn has thrown in the towel and acknowledged that new demographic realities are a permanent and irreversible fixture of Irish society. Under these circumstances, Quinn tries to look at the bright side and finds it in the hope that migrants will be more inclined towards religiosity than secular Irish liberals. Clearly Quinn recognises the transformative impact mass-immigration will and is having on Ireland, but retreats from actually casting a moral judgement on this demographic upheaval. Instead, he takes solace in a pipedream that the Ireland of tomorrow, while it may not be Irish, will at least be religious.

Religion in a non-Irish Ireland

Quinn’s choice of the phrase ‘religious’ over Catholic or even Christian is telling. One could easily point to the influx of Islam, but perhaps more truthfully the future of religious expression in Ireland, particularly with the hollowing out of any serious belief in Catholicism, is likely to be reflected in an explosion of a hodgepodge of new religious movements. Where religion exists in the ‘new Ireland’ it will be as a miscellany of new age movements, tantric eastern aficionados, evangelical Protestant groupuscules, and nondescript spiritualist tarot-card readers. This will inevitably run concurrently with a high degree of mountebankery and charlatanry. We have already seen the embers of these new movements, but in the future they will undoubtedly play a larger role in what’s left of the social fabric.

Any serious Irish Catholic, who may instinctively prioritise the survival of Catholicism over other issues like opposing mass-immigration, needs to recognise that for Catholicism to ever be revived it must literally remain the faith of our fathers. It is easy to write off the Irish people as irreparably liberal, after all didn’t they vote 2/3 for abortion and gay marriage? But a deluge of immigration, particularly from the third world, would not lead to a more ‘conservative’ Ireland. Any liberal worth his salt would tell Quinn, rightly, that immigrants will be integrated into the dominant culture and become absorbed within it. In a hyperglobalised society filled with an amorphous culture which extends across the west, immigrants would undoubtedly be assimilated into the culture that infects this outpost of the western imperial world. Not into Irish culture per se, but into hyperglobalised liberal culture – with ‘Irish’ characteristics.

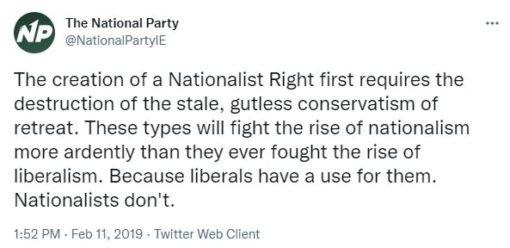

Irish Conservatism

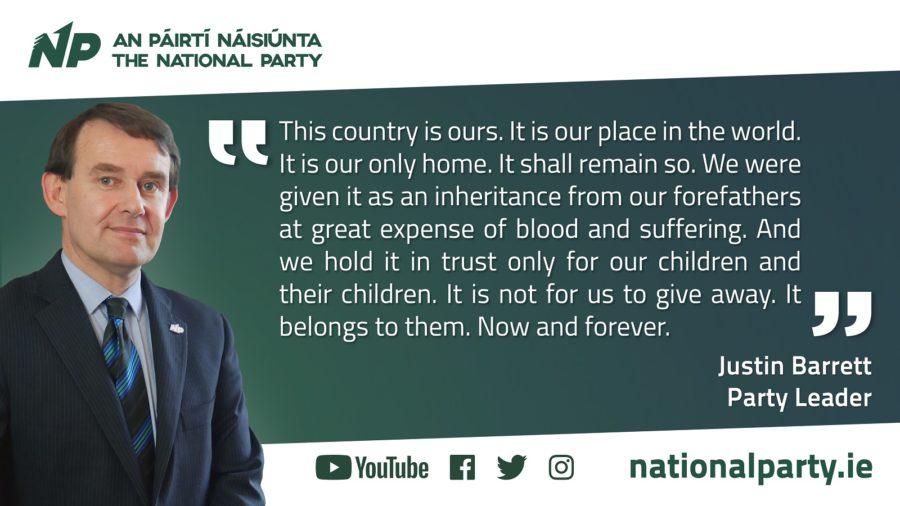

Moving beyond the issue of the confessional makeup of a future non-Irish Ireland, the underlying theme of Quinn’s tweet illustrates all that is wrong with Irish conservatism. As mentioned, there is obvious fatalism in Quinn’s claim. He takes solace in a delusion about what a future non-Irish Ireland will be like, but he implicitly sees it all as inevitable.

There are several of these conservative Cassandras in modern Irish public life, who produce reams of column inches arguing that conservative and Christian voices need to be heard and taken seriously in a democratic society. They are the true democrats, you see. They desire the widest possible inclusion of voices and perspectives on all issues – liberal and conservative, left-wing and right-wing, pro-life and pro-choice. After all, the widest possible consultation is best for all of us, as the late Marquis de Condorcet scientifically proved. But the simple truth to burst this illusionary bubble is that Irish liberal democracy is already affording these people a say – that is why they’re given columns and an occasional seat on panel debates as befits their representative status in society.

In liberal Ireland, conservatives still wear the mark of Cain on their foreheads – the unforgiveable ‘crimes’ of the Catholic Church can never be forgotten – and for that reason conservatism will never again be given an authoritative say on any issue. Seeing this, they have tried to appeal to the centre and make their case on the grounds of ‘fair play’ and that it’s worth listening to everybody’s tuppence-worth opinions. Like a smug schoolmarm at the back of a classroom, they lecture and drone on and quote Locke – because in addition to being the true democrats they are also the true liberals. This is clearly not a winning strategy.

It cannot be said enough that mainstream Irish conservatism is a blight on the body politic. In trying to appeal to the centre ground and appear pitiably respectable, the Quinns of this world have tried to out-liberal the liberals. Unlike in the United States of America, where conservative ideologues have been dragged kicking and screaming to the right, Irish conservatives remain stuck in the mud and begging for occasional scraps from the high table of the dominant globalised worldview. But they will go hungry, as without access to political capital they remain beggars and paupers in a political system which thinks of them as relics and anthropological oddities of a bygone age.

This article was submitted by a National Party member. If you would like to submit an article for publication on the National Party website, follow this link.