Irish history is replete with episodes of objective injustice and cruelty. More often than not, these episodes of barbarity stem from this island’s subservient relationship with Britain. The innumerable tragic incidents and injustices which have befallen Ireland since 1169 have been memorialised in poems, ballads, and the collective memory of the people. It is a unique fixture of the tragedy that is Irish history that when ‘Bloody Sunday’ is mentioned, the inevitable question “Which one?” must be asked. Just as today marks fifty years to the day since the events of Bloody Sunday in Derry 1972, this event was itself predated by approximately fifty years by the ‘original’ Bloody Sunday in Dublin 1920.

While the Bloody Sunday of 1920, when Black and Tans mercilessly opened fire on civilians attending a football match in Croke Park, provoked widespread anger and consequent support for the IRA’s War of Independence effort which marked a turning point in that conflict, the Bloody Sunday of 1972 resulted in a dramatic albeit short-lived burst of anger across Ireland but failed to produce a water-shed moment that would lead to a resolution. That the widespread anger in 1972 was never marshalled towards achieving a British withdrawal from Ireland is lamentable.

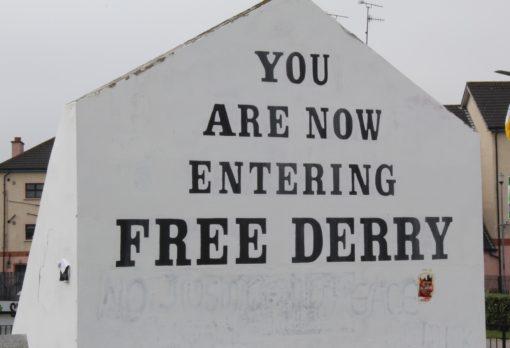

Derry’s Bloody Sunday occurred suddenly in the afternoon of 30 January 1972, when civilian protestors marched against the policy of internment without trial. Fourteen innocent people, all Catholics, were killed by British soldiers from the Parachute Regiment who opened fired on the protestors without provocation. Reports of this massacre were broadcast globally and drew the attention of the world to the erupting conflict in Ireland.

Derry city, the scene of these events, had been partitioned into the new Northern Ireland in 1920 along with other majority Catholic territories such as the counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone, alongside parts of south Down. When the Treaty was signed on 6 December 1921, many people in Derry and across majority-Catholic regions of the North welcomed it, believing that the promise of a boundary commission would invariably cede these Catholic territories into the new Free State. Meanwhile, throughout 1922 the pro-treaty leaders such as Michael Collins took a keen interest in ensuring areas such as Derry city would become part of the new Free State. Until the time of Collins’ death in August 1922, the Provisional Government paid the salaries of Northern civil servants and teachers and instructed Nationalist-controlled councils to recognise the Free State as their government. However, the death of Collins and the new policy adopted by the Free State government directly led to the ramshackle boundary commission in 1924 which sealed the fate of Catholic areas such as Derry city within the bitterly sectarian Unionist-dominated Northern Ireland.

The fate of Irish people trapped north of the border was characterised by extreme discrimination. The eruption of widespread and uncontrollable violence in 1968 marked a turning point which seemed to endorse the description of Northern Ireland as a ‘failed political entity’. Bloody Sunday was met in the south with palpable public anger which has seldom been repeated. The most popular memory of this public anger was the burning of the British Embassy in Merrion Square by protestors on 3 February 1972. Undoubtedly, Irish public opinion was incensed by the events in Derry, which led to a national day of mourning and numerous strikes across Ireland. Enraged frustration often expressed itself with overt sympathy for armed intervention in the North and allusions to Irish history, including the original Bloody Sunday, 1798, and the Cromwellian Invasion. The near-universal framing of the events of January 1972 in such terms across Ireland led many to believe that a Rubicon had been crossed.

Although the initial reaction to Bloody Sunday was marked by high tensions, this anger soon dissipated. A regrettable ennui and disaffection with violence in the North set in across the south. A lack of southern leadership, under the Jack Lynch government, was an obvious cause for this. Lynch failed to grasp the nettle of the Northern problem while the Irish media, which gave platforms to the views of public intellectuals such as John A. Murphy and political voices such as Conor Cruise O’Brien, slowly wore down bubbling Irish radicalism through their repeated deconstructions of Irish republicanism. This would not be the first time that the Irish media manipulated widespread public indignance with a particular tragedy and misdirected this fervour in a self-serving direction. Thus, instead of being a watershed moment which saw a rebirth of Irish radical nationalism and breeding a determination to finally shake off the manacles of British Imperialism, Bloody Sunday birthed an extreme solipsism and marginalisation among Northern nationalists. An event which should have been a catalyst in the process of national redemption was squandered.

On this fiftieth anniversary of the events of Bloody Sunday 30 January 1972, it is vital that we reflect on one of the most horrifying events of recent Irish history. Events such as this should not be viewed in abstraction, as simply random occurrences of violence happening in a decontextualised ‘tribal’ environment. Bloody Sunday must be remembered as an instance of British oppression in Ireland no different from the executions at Ard na Caithne in 1580, the pitch-cappings of 1798 or the callous murders at Croke Park on 21 November 1920. Bloody Sunday is part of a continuum of British cruelty in Ireland. Only by achieving full and complete sovereign independence can Ireland, as a unified country, build prosperity and happiness for its people.

This article was submitted by a National Party member. If you would like to submit an article for publication on the National Party website, follow this link.