The Irish are a race who are in the process of discarding their entire practical and theoretical existence, not out of duress or necessity but seemingly out of conformity. Even a sentence that begins with “The Irish are a race” will cause them now to cringe with embarrassment, apologise to the ubiquitous foreigner in the room, and change the subject. Probably click off this page and move as quickly as possible onto something more digestible. Yet it was a perfectly ordinary phrase only a few short years ago.

The trend-driven, disposable identity of the twenty-first century Irish man or woman is perplexing. On one level defined completely and positively by the fact that they are Irish, a subject that animates their every social interaction. And yet, on another level, self-depreciating to the point of self-destructive when it comes to actually defending it. What seems in the case of the former to be obsessive, proves in the case of the latter to be superficial.

Two Irish people meet in a foreign country. And immediately greet one another with a form of assurance and recognition. We see the sense of familiarity and the virtue of belonging. Does anyone in their heart of hearts believe that nationality and blind partiality to one’s countrymen has no value whatsoever? Let them step up then and defend it, if they are not too embarrassed to do so. For, in effect, that is the case in Ireland today.

The very exodus which has shattered Irish nationality, the very folly of boom-time extravagance that preceded the most recent calamity and most recent exodus, hang on the Irish psyche like the proverbial albatross. No other country in Europe seemed to face the economic crisis of 2008 with the sense of shame and embarrassment that so many Irish people did. It took almost a decade before they recovered enough self-worth to even march in the streets in indignation.

Other Western European countries had their dark night of the soul many decades ago. And are in some cases starting to recover. But Ireland was late to the party and is still running to catch up. Never did a country run so blindly into the full blown narcissism of consumer capitalism, discard so quickly the scaffolding of religion and tradition, which for most of mankind is the flawed but necessary basis of social order, and then crash headlong into staggering economic servitude. A decade or more later, Ireland is a corporate zombie nation with strange new corporate religions, flags, symbols, rites. And to top it all, a kind of collective amnesia about exactly what has happened to us. Modern Ireland is a perpetual present. And the memory of the past is treated with the awkwardness of a drunken blackout. Something to be forgotten and suppressed in the urgency of the moment.

Religion, Nationalism and the Past

The Irish have been known to cut themselves off from their origins. As much as the Irish language was beaten and starved out of us, it was also made to seem backward and unimportant and embarrassing. Parents would make sure their children spoke English because that was the language of economic survival. It was the language of the modern world. And in subsequent times, the mismanagement of the Irish language revival, by allegedly Irish governments, would itself become a source of embarrassment. For if the loss of a language can be put down to accident or misfortune, the failure to revive it seems like carelessness.

Is embarrassment a motivating factor in twenty-first century Irish identity? If so, what are they all so embarrassed about? For one thing, their attitude to the past is laced with embarrassment. The past referring mainly to a certain nightmarish vision of mid twentieth century Ireland which the present Ireland tries too hard to be a reversal of. How could we ever have been so backward? So dark? So rainy? So oppressive? But they quickly assure whoever will listen that we don’t behave like that anymore. We’ve grown up. We’ve matured. We’ve changed. We kill with kindness now.

They are embarrassed about the past in general and Catholicism in particular. Most of this is obvious. The whole culture cringes to think that anyone ever believed in God or knelt inside a church. God help us, how could a dark, oppressive, rainy religion have ever dominated Irish life? How completely and utterly embarrassing. And how they flee so excitedly in the opposite direction. As though retreating in embarrassment from something were a form of agency. Or even a form of rebellion. As if the sins of the past could be redeemed so conveniently by the sins of the present. The vague idea that this is a modern country now like France or England, propels them forward, stumbling towards the rumour of progress.

Nationalism is more complicated, mainly because partition continues to animate it. But in substance, particularly in the south, it has been abandoned. The implications for our national sovereignty presented by our membership of the European Union have not so much been brushed aside as ignored completely. Which is easy to do because the issue does not yet engage the Irish mind. A surprising number of Irish people still believe that the EU came dutifully to our rescue during the financial crash. And Irish confidence in the EU is substantially higher than it is in the current Irish government.

Meanwhile, the Left Republican factions talk out of both sides of their mouths on the subject. Both on the EU issue and on the national question itself. They are forever introducing nationalist imagery and forever phasing it out. Stuck in some pragmatic half-way house between OSF and the Workers Party. Afraid to abandon the accouterments completely but increasingly embarrassed by them. What did Bernadette McAliskey say at the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of the Bogside? She said we need to “get out of the nationalist conversation.” And that has been the real Hard Left position since the 1960s. In truth, since well before that. Nationalism to them is something dark and reactionary. And in their hearts they rue the day that Connolly marched into the GPO under the Starry Plough, fettering as he did the socialist revolutionaries to the cause of nationalism. For a hundred years they have striven to unfetter themselves from that one event. Either by deracinating its meaning or by disowning it. “They will not understand” Connolly is reported to have said shortly before his execution. “They will all forget that I am an Irishman.” They have forgotten. Or else they are embarrassed to remember.

And what of the many Irish people who have no political leanings? After a night of drinking, a few rebel songs may make an appearance. But in the sober light of day, nationalism is far more contentious. Outside of occasional ritual expressions it exists only in superficial forms. The National Anthem playing in Croke Park elicits an almost heartbreaking display of tribalism and passion. But who can bottle it? Who can put it to a purpose greater than an annual sporting event? Who can put it to work at saving Ireland?

The near total derision with which the New IRA march through O’Connell Street was treated, is telling. And it had perhaps less to do with Lyra McKee’s recent murder than with a collective awkwardness towards the juxtaposition of paramilitarism against the type of new, post-national Ireland she was seen as representing. Or even the basic anachronism of national assertion in a capital city which appears more foreign by the day. Beyond a few IRA memes on the Internet or the familiar annual commemorations, any practical iteration of national struggle is too embarrassing and out of place in the twenty-six colonies that are the twenty-first century “Republic”. And upon appearance they elicit the usual coping strategies of classist jibes and schoolyard mockery. The bottomless derisive irony of Late Capitalism which in most Western countries is considered increasingly out of date, but in Ireland persists.

The comfort derived from the popular distinction between xenophobic Brexit nationalism and a warm and fuzzy Irish nationalism, is really no more than the smugness of conformity. The smugness of being on script while the person next to you loses their place. And the embarrassment so many Irish people seem to feel on behalf of the daft Brits is really an expression of how hemmed in they have become by the narrowness of the new culture. The claustrophobia of the vaunted “openness”. The tedium of the “diversity”.

Why is this absurd? Why do we know this is superficial? Because nationalism is not warm and fuzzy and convenient. It is something entirely different. And easy as it is to make fun of Brexit and the Brits, it takes a lot more nerve to look deeply at ourselves and ask “Are we not now a people worthy of derision and parody? Have we not sunk lower than the most abject depths of our ancestors? Have we not abandoned all that is fundamental and life-giving? Have we not abandoned even the most basic idea of surviving as a people?”

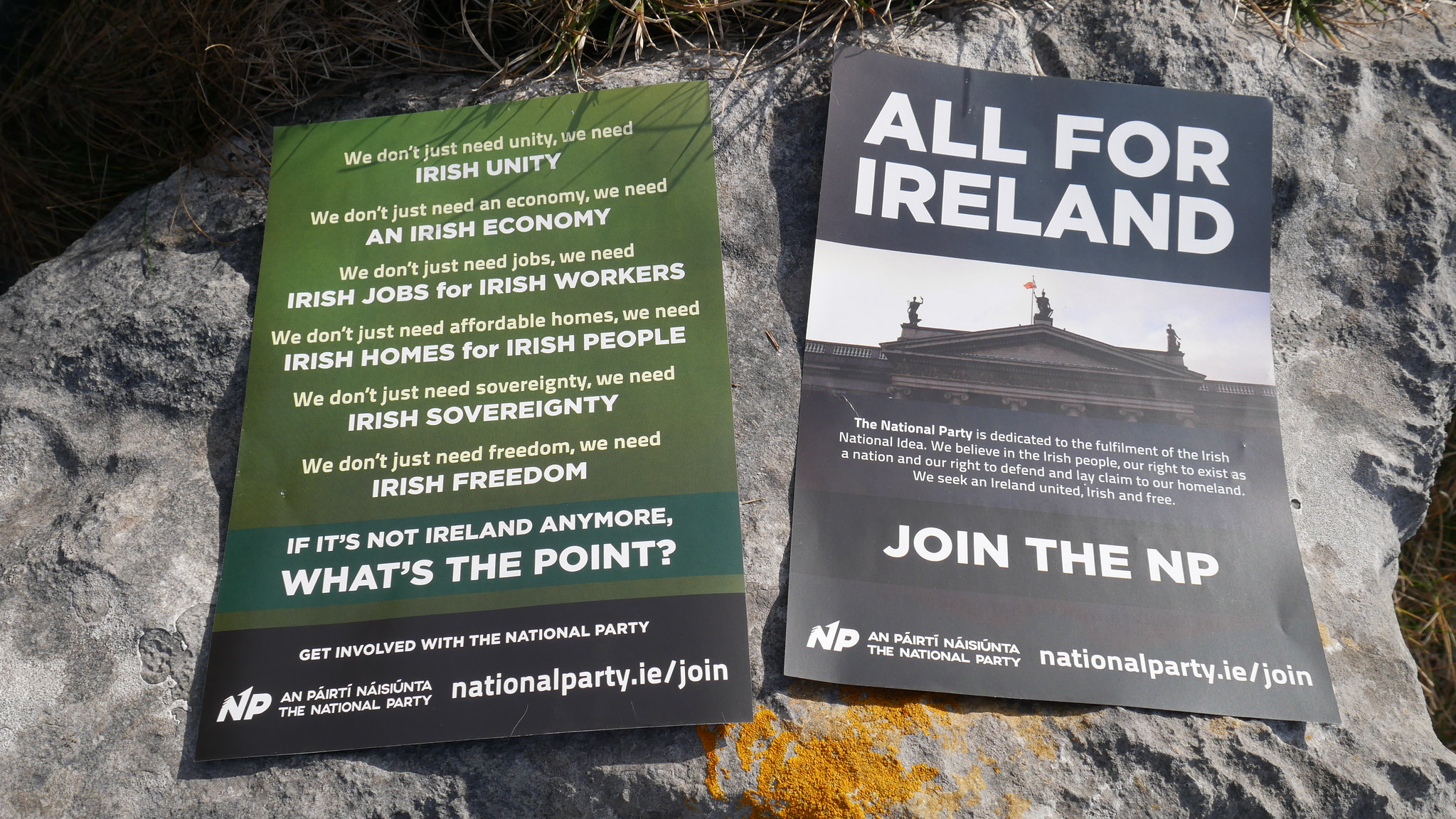

Nationalism is a fundamentalist assertion. And nothing is more terrifying to a society that believes in nothing than a person who believes in something absolutely. That Ireland should belong to the Irish? This is an embarrassing assertion now. That the Irish people have any value in and of themselves and that this should be protected? Each of these are embarrassing assertions. That any definition or category pertain to what it means to be Irish? You may as well not even go there.

Liberal Ireland and Post-Nationalism

The same factors extend to every alleged social revolution in contemporary Irish life. Almost all of which are just things we picked up from American television shows. The Californian entertainment industry remains the most significant influencer of culture and morality on the planet and, unlike the Catholic Church, its marketing people are very good at dealing with sexual abuse scandals. It took them only a few days to turn a potentially industry-shattering story into the harmless, Oscar-friendly #MeToo movement.

The only revolution happening in Ireland today is the succession of corporate social-media fashions, trending always towards relativism in the areas of nationality, identity, gender and morality. The socialist revolutionaries who Connolly feared would “not understand” have long ago been assimilated into the triumphant paradigm of social and economic liberalism. We are living in an age that aspires to post-nationalism. And the forms of identity politics which pertain are attempts at fracturing national forms and reducing society to individual units of production and consumption.

In recent memory Irish people have danced and cheered on the streets for two stupendous liberal victories. Both brought about under a Fine Gael government but with full support from the Left and full support across all major parties. Two victories which more than anything else have defined Liberal Ireland. Both were victories in the social sphere and both distracted attention away from failures in the economic sphere. Both were landslides.

What were the deciding factors in the overwhelming Yes votes in both the abortion and homosexual-marriage referendums. How many people were true believers? And how many just felt obliged to go along? Never underestimate the importance of social conformity in carrying through a revolution. The marriage referendum was won not on the argument for the extension of marriage as an institution but on the embarrassment to defend or define the boundaries of marriage itself. “Love is Love” might have been a tautology. But was it worth embarrassing oneself to point that out? And was it all that important anyway? It’s not like they were trying to remove the protection of the unborn child from the constitution, now was it? Well, in the end they did that too. Same arguments. Same tactics. Same people. One victory on the back of the other. And the same flag was flying at the end. And it wasn’t the Irish flag.

When groups like SIPTU march down Barrow Street, in support of monopoly capitalism and wage deflation, their format now is basically a Gay Pride parade. That has become the default branding for State subsidised moral righteousness. Surprisingly, for a country which has abandoned the belief in transubstantiation, every other form of trans is now accepted without question. The LGBT+ brand cannot just be dismissed, since it has de facto become the surface ideology of corporate consumerist American hegemony. And therefore of Irish media culture as well. By accident or design it provides the ideal representation of the individuated consumer. Transient, materialistic, self-involved. The ability to pick and choose one’s gender and sexuality being the consumerist ideal made flesh. Presided over, of course, by the many-coloured flag (now flags) for which countries are occasionally liberated by missile attack. The flag which, more than any other, has taken the place of national or religious forms. Even more so than the ubiquitous but passionless EU flag, it is probably the most officially sacred symbol in Ireland today, though in fairness we are living at the peak moment of its ascent to cultural dominance. It is the flag of post-nationalism.

What is it that allows the rainbow flag to fly over Irish schools or over the GPO in Dublin or adorn Free State squad cars? Is it some moral righteousness or hysteria which has taken hold in the average Irish person? Some incredible collective zealotry that has raised this object like a national emblem in the zeitgeist of the populace? Probably not. It probably has more to do with the social consequences of rocking the boat. Or the fear of being called names.

To take a very obvious recent example of this, any fool can see that the rhetoric around transgender politics is absurd and even dangerous. Especially in relation to children, who seem increasingly to be the target market. All of these colourful iterations are, at the end of the day, market opportunities for someone. But since most people can see that a child shouldn’t be allowed to choose their own gender, the issue has created a mini civil-war within western progressivism. The Irish version of this was the crucifixion of Graham Linehan. But other than in private, very few ordinary people have the nerve to call it out. Even when it is inserted into the school curriculum, and taught to their children, people remain silent. It is the most straightforward example one can give of a society shackled by conformity. And while some of these examples may seem trivial, they end up meaning quite a lot. If you’re not prepared to step out of line to protect your own children, then you’re probably not prepared to step out of line for any reason. If gender is relative then so is nationality and so is everything else. And if everything is relative then there is finally nowhere left to stand or make a stand.

On the positive side, there is only so demoralised, apathetic or conformist a society can get before a dissident section of that society begins to crystallise. There is evidence that that is already happening. And we must keep in mind that it does not take a majority of opinion to change a country. It only takes a well organised and vocal minority. Starting with a solid core. The number of people who form the ideological core of contemporary Irish society is relatively small. But they hold sway over an apathetic majority.

The Irish people on the whole are not true believers in any of this. They believe basically in very little anymore. They go along to get along. They avoid if at all possible making fundamental statements. And they avoid criticising the dominant belief system which is unanimous across State/ NGO/ media/ corporate platforms. The dominant belief system is quite clear in what it demands. A supranational paradigm, a fractured, atomised society and the complete and total destruction of the Irish people. That is to say, a scenario where it is simply not plausible to talk anymore of an Ireland or an Irish people. Where it is not possible for us to see ourselves anymore as a coherent nation. Like everything in which people have ceased to believe in, it will in the end have ceased to exist. If you are too embarrassed to be Irish, if you are too embarrassed to assert Irish nationhood in the modern world, if you are too embarrassed to make distinctions between who is Irish and who is not, then soon there will be little left to discuss on the matter. It will be over. The matter will be closed. The plain fact is that if you’re not prepared to make a distinction between who is Irish and who is not, then how do you even know you’re Irish? And what could be more embarrassing than that?